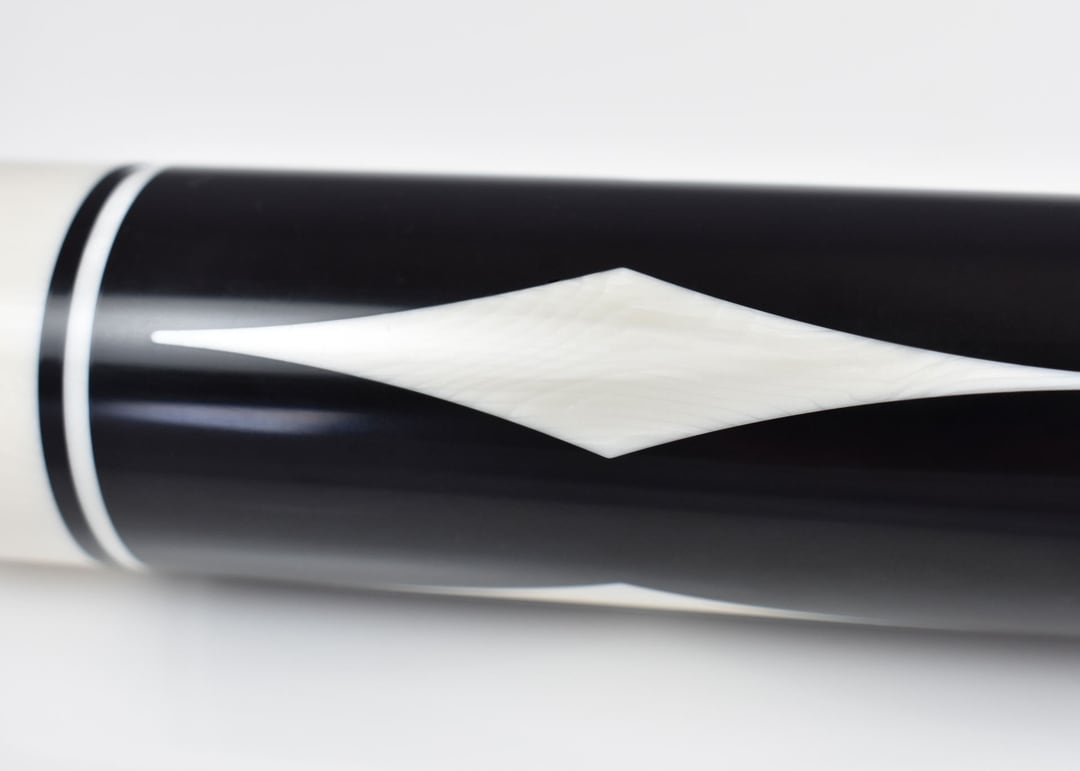

We have paid attention to excellent technical and mechanical properties during the development of the newest high-quality ivory substitute Elforyn Super Tusk. As well as an unique similarity to real ivory. An unbelievable imitation of the color, grain and “Schreger lines”. The structures are visible even in the smallest applications and create a peerless look on each product.

„Schreger lines“ are visual artifacts that appear in the cross-section of ivory. They are commonly referred to as crosshatching, rosette shaped, alternately light and dark colored structures. The intersections of the „Schreger Lines“ are forming the checkered typical angles of ivory charisma.

kg/ml Density

(DIN EN ISO 845)

Hardness Shore D

(DIN 53505-D)

N/mm Tensile strength

(DIN EN ISO 527)

Elongation

(DIN EN ISO 527)

N/mm Flexural strength b-4%

(DIN EN ISO 178)

N/mm E-Modulus

(DIN EN ISO 178)

The principal source of ivory is elephant tusks. Other possible sources include the teeth of the mammoth, hippopotamus, wild boar, walrus, sperm and narwhal whales. Each different type of ivory has different colouring and properties. Under the microscope and by means of spectroscopy it is even possible to differentiate ivory products between Indian and African elephants.

The most valuable ivory comes from the narwhal and used to be valued as highly as gold. Walrus ivory is similarly very valuable and the reason why the walrus population has been strongly decimated.

The elephant has long been hunted for its ivory. Elephant bulls grow tusks to a length of two to three metres. Like human teeth they consist mostly of dentin. Ivory has been coveted for thousands of years as a base material for artistic carving, sculptures, inlays and to impart a sense of luxury to every-day articles. It was the Japanese and Chinese who perfected ivory-carving as an art-form, yet ivory carvings were also popular in Germany. Today, East Asia remains by far the biggest market for ivory. In Japan it is used, for example, to make representative name-seal stamps, so-called ‘hankos’. The trade in ivory has long been the greatest threat to the African elephant. In the 1970s and 1980s numbers declined dramatically, from around 1.3 million to less than 400,000 animals. In 1989 the trade in ivory was banned internationally.

In the 19th century most of the ivory was used to manufacture billiard balls, keyboards and knife handles, but also for brush-covers, umbrella and other handles, combs, fans, rulers etc.

The company Heinr. Ad. Meyer reported that in the years 1879 to 1893 an average of 284,000 kg of ivory was imported from West Africa and 564,000 kg from East Africa, making a total of 848,000 kg, while 11,000 kg came from the Indian peninsula, 7,000 kg from Rangoon, Chittagong etc. and 2,000 kg from Ceylon – Sumatra.

Subsequently, annual global consumption was at its highest in 1879-1913 when it stood at 848,000 kg. The majority ended up in Europe, 535.000 kg, and was divided between: handles for knives and cutlery 214,000 kg; combs 138,000 kg; keyboards 112,000 kg; billiard balls 42,000 kg. The remaining 29,000 kg was used for brush handles, for tools and door latches as well as dishes for creams, glove-stretchers, toggles and other industrially manufactured products. In the whole of Europe only an average of 6,000 kg per year is used to produce ivory carvings.

In spite of the ivory trade ban, poaching continues to raise its ugly head and the illegal trade in ivory is flourishing.

Ivory is smuggled from different African countries as far as Asia, where the ‘white gold’ is sold at prices five times higher than in Africa. The principal markets for this raw ivory are in China, Thailand and Vietnam, where it is transformed into high-quality carvings.

A recent investigation in eight countries in Asia revealed over 100,000 kg of ivory carvings in shops. Probably over 80% of these carvings are sold in Thailand, primarily to tourists and business people from Europe. The Germans, Italians and French turn out to be the main customers for ivory carvings. The authorities in Asia turn a blind eye to the sale of these products in markets and shops. Financial inducements enable smooth passage across borders and certain elements of the military and police are directly involved in the poaching. As a PRO WILDLIFE spokeswoman explains, “The growth of tourist numbers in South East Asia threatens to further fuel the illegal trade in ivory.”

From time immemorial the most important ivory substitute for inlays and small carved figures has been bone material.

The main component of vertebrate bone is hydroxyapatite. Chemical composition varies greatly according to age, genus and nutritional status. The bones of old cattle, for example, contain less cartilage material (ossein) and more mineral salts than do the bones of younger animals.

Bones are used as an ivory substitute in turneries, carving workshops and button factories to manufacture knife-sheathes, stick and umbrella handles, keyboards, chess-figures, rings, needles and buttons.

In the ivory town of Dieppe even horse and cattle bones were widely used to manufacture inexpensive Christ and Saint figures. In the 19th century ivory nuts were also used to manufacture small objects.

The tagua nuts, sometimes also called ivory nuts, come from the ivory-palm (Phytelephas Macrocarpa), where they grow in bunches up to a weight of 12 kilograms. The palm is native to the equatorial region of Central and South America and thrives along the Rio Magdalena in Columbia. After the nuts have been harvested, they become dry and hard, protected by a crusty, scallop-shaped shell. We also know the tagua as the ‘stone-nut’, because it becomes extremely hard. However, it is not a petrified fruit.

A medium-sized fruit is around three times four centimetres in size. It is basically rounded in shape, but with four slightly flattened sides, one end that runs towards a point and a slightly concave stalk end, similar to the stalk recess you find on an apple. The tagua nut is not at all poisonous and, when harvested, it is even soft, edible and sweet. Tagua ivory has been traded as a raw material for over 200 years. Indeed, for over one hundred years the Japanese have used it to carve Netsuke figures and since the Victorian era tagua has been used to make jewellery. It was also used widely to produce buttons, until plastics became popular in the middle of the last century. Over the last few decades craftspeople have found tagua-nut ivory suitable for turned and carved needle boxes, dice, thimbles, fine carvings and other long-lasting and attractive objects.

We have managed to combine the best of all previously available ivory substitutes in just one : Elforyn Super Tusk. In appearance and characteristics the highest QUALITY – MADE IN GERMANY. Always use Elforyn Super Tusk instead of real ivory.

No matter which ivory replacement you choose, the end is always the protection of species!

Bachmann

Kunststoff Technologien GmbH

Rudolf - Diesel - Straße 2

63322 Rödermark

Germany

Phone: +49 (0) 6074 94 3 94

Fax: +49 (0) 6074 98 5 44

Email: info@elforyn.de

Internet: www.elforyn.info

CEO: Pascal Julien / Marcel Julien

VAT-no.: DE113533031

Trade Register: Amtsgericht Offenbach am Main

Register-No. HRB 32700